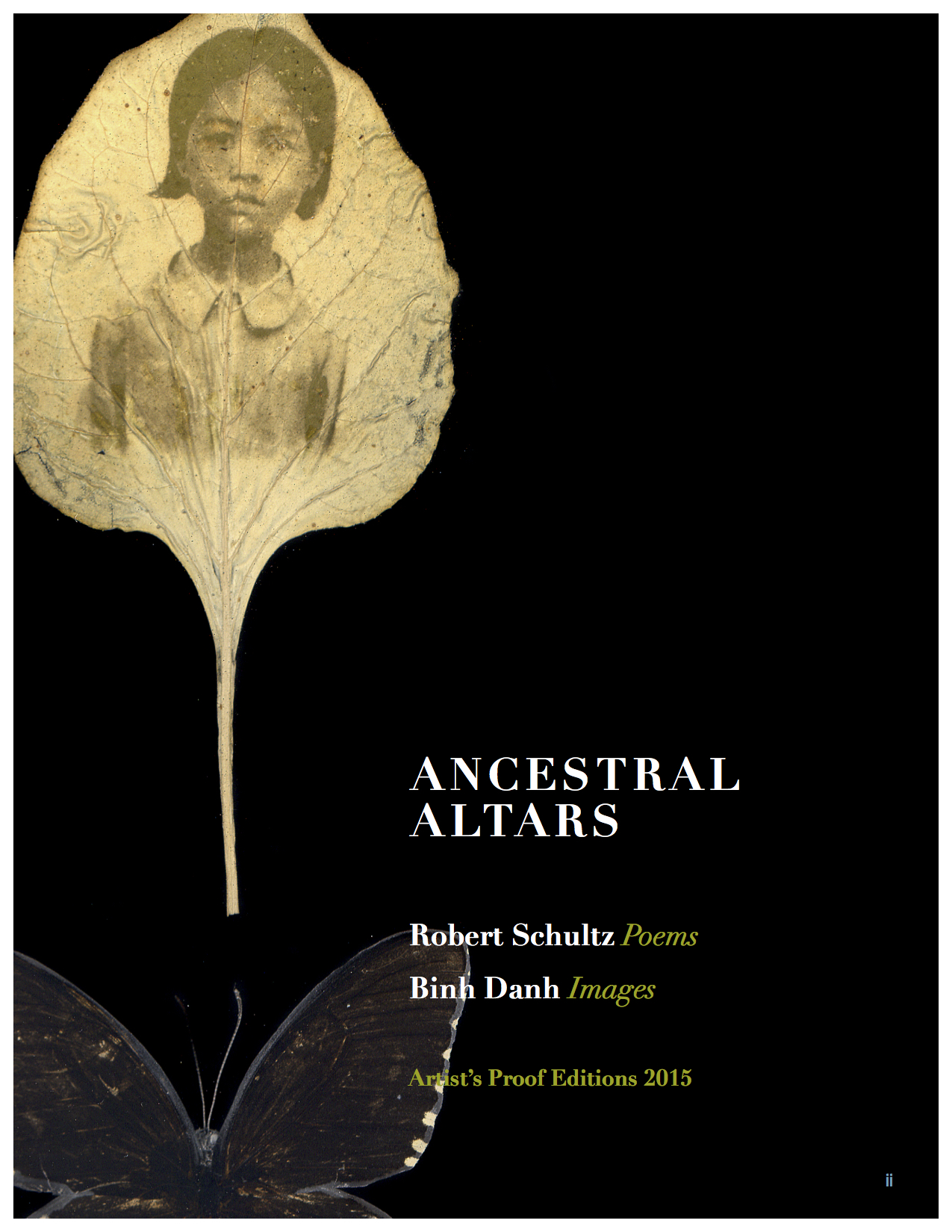

Ancestral Altars

Robert Schultz, Poems

Binh Danh, Photographic Images

A multi-touch, multi-media book available on iBooks.

“Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Night” Moving Poem

“Ancestral Altar No. 7” Moving Poem

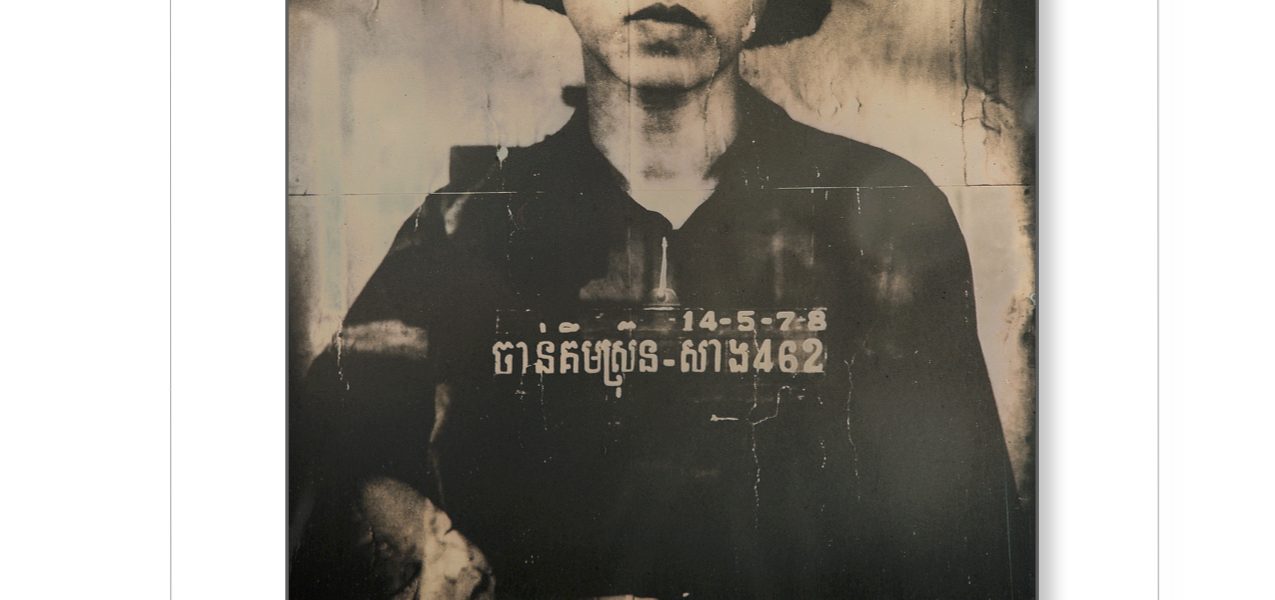

Some years ago, Robert Schultz, a poet, witnessed an exhibition of photographs printed in the flesh of leaves of trees and plants, portraits of war-worn Vietnamese and of Cambodians documented in the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge.

These chlorophyll prints, as they were called, were made by Binh Danh, a Vietnamese-born American photographer. About his method, Binh Danh wrote, “This process deals with the idea of elemental transmigration: the decomposition and composition of matter into other forms. The images of war are part of the leaves, and live inside and outside of them. The leaves express the continuum of war. . . As matter is neither created nor destroyed, but only transformed, the remnants of the Vietnam and American War live on forever in the Vietnamese landscape.”

Robert Schultz responded to Binh Danh’s chlorophyll prints with a series of poems, which he composed formally, as if in grief after suffering. He turned back, he said, to the “circular movement of traditional forms (the villanelle, sestina, pantoum) to enact cycles of natural and historical recurrence.”

These poems and those images are present in Ancestral Altars. Here, the reader may encounter them as if in company with the poet and the artist, and yet, in contemplative solitude. In their beauty and dignity is compassion.

In its design, incorporating moving-poems, audio, and a gallery, Ancestral Altars is the response by Artist’s Proof Editions to their poems and images. In this iBook, a reader hears the poems spoken by the poet, carried on his breath as, simultaneously, s/he taps to open and examine the enleafed or daguerreotyped images, digitized, that called them forth.

The reader can view, intimately, Binh Danh’s leafprints and daguerreotypes, as s/he listens to Robert Schultz telling his poem for his friend and co-worker.

. . . . . .

I sit before ancestral altars

And the dead have questions:

“How could this have happened?”

I have gazed for hours at their startled faces.

He makes portraits out of sun and leaves,

Builds altars for the lost, a place.

About the work of these artists, commentators have written:

Robert Schultz’s books include two collections of poetry, Vein Along the Fault and Winter in Eden, a novel, The Madhouse Nudes, and a work of nonfiction, We Were Pirates: a Torpedoman’s Pacific War. He has received a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Award in Fiction, Cornell University’s Corson Bishop Poetry Prize, and, from The Virginia Quarterly Review, the Emily Clark Balch Prize for Poetry. He attended Luther College and received his graduate education at Cornell University. He has taught at Luther, Cornell, and at the University of Virginia. He was the John P. Fishwick Profess of English at Roanoke College (2004-2018) and continues to live and work in Salem, Virginia as an author and artist. Robert Schultz and Binh Danh have been collaborating on art and poetry projects since 2008.

Robert Schultz’s books include two collections of poetry, Vein Along the Fault and Winter in Eden, a novel, The Madhouse Nudes, and a work of nonfiction, We Were Pirates: a Torpedoman’s Pacific War. He has received a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Award in Fiction, Cornell University’s Corson Bishop Poetry Prize, and, from The Virginia Quarterly Review, the Emily Clark Balch Prize for Poetry. He attended Luther College and received his graduate education at Cornell University. He has taught at Luther, Cornell, and at the University of Virginia. He was the John P. Fishwick Profess of English at Roanoke College (2004-2018) and continues to live and work in Salem, Virginia as an author and artist. Robert Schultz and Binh Danh have been collaborating on art and poetry projects since 2008.

Binh Danh has emerged as an artist of national importance with work that investigates his Vietnamese heritage and our collective memory of war, both in Viet Nam and Cambodia—work that, in his own words, deals with “mortality, memory, history, landscape, justice, evidence, and spirituality.” His technique incorporates his invention of the chlorophyll printing process, in which photographic images appear embedded in leaves through the action of photosynthesis. His newer body of work focuses on nineteenth-century photographic processes. His work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Art, the Corcoran Art Gallery, The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the George Eastman House, and many others. He is currently a professor in the Department of Art and Art History at his alma mater, San Jose State University.

Screenshots from Ancestral Altars

You must be logged in to post a comment.