I would like to offer a preview of a manuscript I’ve completed, called Orphans and Strangers, a work of nonfiction. It tells of a river trip I took in 1984, under the guidance of a remarkable woman, into the Alaskan Interior: a voyage into life, death, and coming back.

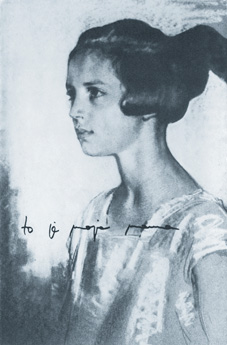

It is dedicated to this woman, who is called Malfa Ivanov (1933-2004):

“You could say we are a tragic people. But, really, we like having fun.”

To the Reader

More than a decade ago, I began writing a counter-memoir about a remarkable woman. She was Alaska Native, a wife, mother, grandmother, businesswoman, and educator. When I lived in the Alaskan Interior, she became my second mother. At her request, when I wrote about her, I called her Malfa Ivanov. I had introduced her earlier, in Narrow Road to the Deep North, and an eminent novelist had told me he found her the most interesting person in the book. There was more to say. I hoped to portray her, often in her own words, as she had revealed herself and her world to me. She was my subject; I was the observant narrator. I had traveled with her and her husband on the barge they ran and seen the Yukon, the Koyukuk, the Tanana through their eyes as well as my own. I thought this was noteworthy. I thought that a woman’s voice would be good, too, for portraying a complex Alaska to readers in the world Outside. The work was consolation following her passing.

But the writing called up a long-stifled memory, of a desperate moment when her words flayed me, a white person, and I was forced to enter the narrative and to reexamine that person I was and my own part in the story, even as I wrote it.

The account centers on a crucial year in the mid-1980s, soon after the break-up of the Yukon ice, when Malfa Ivanov takes her surrogate daughter on a haunting voyage on the Koyukuk, Yukon, and Tanana rivers. As the waters flow, Malfa tells the younger woman the story of her life, even as she excavates the real history of her past. They encounter her intricate network of friends and relatives in the river villages; stories about Jesuits, medicine people, Native beliefs, and growing up orphaned in the Mission; the complications of American law and Native sovereignty; the aftermath of a terrible set of murders; and the mystery of a powerful animal, in a country where everything that lives has its own spirit, which must be respected It was a year of death and serious instruction about death in the midst of life, a somber, brilliant experience.

I’ve said that I was forced to enter the narrative and reexamine the person I was and my own part in the story. Who was that person? A version of her — of myself — as she was then would be: a white woman, born in a small town in Pennsylvania, well-traveled, a practicing poet, trained as an historian of European social thought, with an informed interest in Athabaskan literature. She had left Europe and academia for Alaska with an adventurer’s curiosity, and after a couple of years spent learning the ropes, had gone to work as an itinerant poet in village schools.* From the beginning, it was obvious to her that even the smallest children entered school with a lively sense of story and of storytelling, and that, in making their poems and telling their tales, they came with a communal sense of how stories worked: they brought with them an already-developing sense of form, a poetics. She wanted to learn more about this.

This writer’s responsibility, as I see it, is both to the story and to the people about whom she writes. These are not always compatible. I’ve addressed my disquiet:

I was the writer, the eye, learning to see her country. She and I were also working on a book together, although its subject isn’t clear in my notes, and so I think that, really, she was articulating who she was and whom she belonged to, because something larger was at work in herself that her scrupulous explanations did not wholly cover. When we talked about the book, she told me her most intimate stories. But I didn’t always write them down; they were too personal, I must have thought. I was her ear; I was her reluctant note-taker. I was absorbing the protocol of silence that lay over villages. And if I was an eye in her country, learning to see, I saw more than she meant to show me, and that is part of the difficulty of writing about her all these years later. We talked about writing a book together; but what kind of book was it to have been? Was it this one that I am writing in memory of her? She alone asked me to write it. No one else could have expected to appear in these pages. This troubles me. I am caught in this story: how can I be true to it? As I must be true, and yet, show respect to the people among whom I traveled. And yet, I have no choice, I must go on.

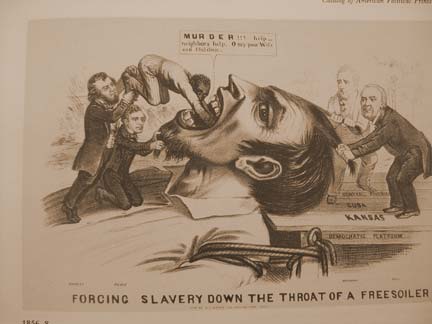

For some time, for family reasons, I put the narrative aside. Now that it is finished — now that I know how it ends — I see that much of the past is still present, and not only in Alaska. Much that I was told and much that I myself witnessed — the violence in communities; the sterilization of Native women; the anguish of spiritual conflict; the imposition of white law on Native customary law; the buried emotional history of suppression; the immensity of what Malfa Ivanov called “the war against women” — is now spoken of publicly. In those years, so much was repressed, among whites and among Natives. Silence sat heavily on the land. It sat particularly hard on women.

Though given always with care and with affection, my second mother’s guidance carried with it a complicated obligation: to convey in writing what she had told me that was important for outsiders to know about her people: but also – this was trickier – what was meant for me, a white woman trying to live in her country, where writers were not always welcomed. Conventionally, ethnology or life-writing might have served, but not for this work. It wanted a form in which I could be true to her, while offering enough context to inform distant readers, who would be Native and non-Native. If I could portray her in literature as if in life, I might embody her kind of knowledge, which though immense, was not abstract, but was implicated in place and relationships; nor did it fall easily into analytical categories.

Yet – here was the trickier part – a more personal matter kept pushing its way back into my narrative, no matter how I tried to delete it. In Alaska, I had carried a certain object: a small, black leather pouch holding a set of toe-bones of a wolverine, a sacred animal of mean and powerful spirit, which might cause harm to others and even to me, and which I didn’t know how to dispose of properly. It was to Malfa I had turned to try to make sense of this burdensome gift. My account became layered with dreams; with things seen and unseen, but felt.

I read back through memory and my journals, through the lens of age and experience. They grounded my story but were incomplete. Interleaved in this narrative is, for context, historical information not available until well after I left Alaska. I respect primary sources. I prefer quotations, not paraphrases. I use footnotes. Following the path of several stalwart independent researchers, a new generation of social scientists both Native and non-Native began to examine the records embedded in Native oral histories, and to recognize that, with guidance from elders and qualified speakers, they could be relied upon as accurate. More recent scholars published critical historical examinations of the transformation of Native lands, the effects on Native tribes, after American acquisition and under American governance. Russian historians examined newly opened records of the Czarist Russian America; translations appeared and fostered reconsideration of the American purchase in 1867, with the Treaty of Cession, and its fateful aftermath. The implications of the Alaska Native Settlement Act (ANCSA, 1971) are still unfolding. On the rivers, we were passing through histories revealed at a slant, as if when light refracts as it enters water.

In the last several centuries, those of us who arrived in Alaska from elsewhere — whitemen, Black whitemen; Russians, Europeans, Americans; explorers, priests and nuns and ministers, prospectors and commercial agents, anthropologists, linguists, reporters, novelists, poets — who wrote of our experience have tended to depict the Great Land in geological time, or from the time of Contact, or in view of our particular involvement, which might include interaction with Native people; or in some combination of the above. Always, its magnificence: land of the Great Weather. Then, just the other day, NOAA announced that Fairbanks, along with several other weather-station sites in the Alaskan Interior, exists no longer in a sub-Arctic climate, but in what is termed a “warm summer continental” climate. A boundary has been re-drawn. I suppose that this event might now mean that the immense Interior, Alaska’s sub-arctic region — where my story occurred — which has long considered itself separate from Outside, now is continuous with it. With climate change comes other change; because of other change comes climate change: a recursive engine, the Anthropocene. Our language, too, becomes altered.

On the Alaskan land there lives, sometimes intermingled with the incomers’ tellings, a prior mode of telling carried down in old stories, expressed in ancient languages in which sound traces and echoes of the Distant Time, the First Beginning. Thus, the importance of literature: of language; of including all that is needed, and nothing that is not; of finding the inner form of the narrative; of telling a true story.

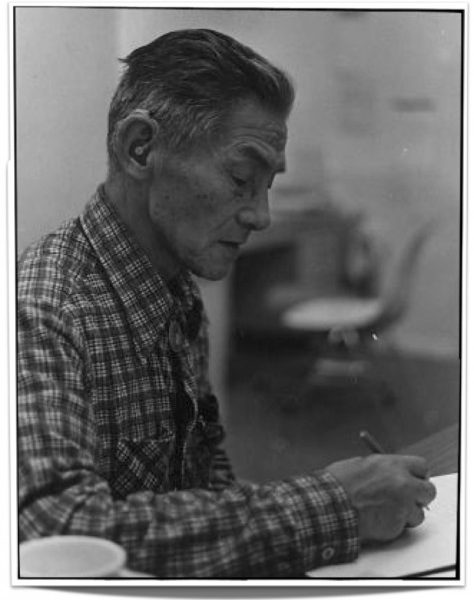

Alaska — the whole North — is a land of dreams, a land of Imagination, through which we are always passing. The late Dena’ina Athabaskan writer Peter Kalifornsky described how his ancestors knew their world: “They lived life through Imagination, the power of the mind.”

What does this mean?

From Peter Kalifornsky I would learn that the stories say that everything that lives has its own spirit, its own life, and this life must be respected. They say that the spirit does not die but returns in a new body. They say that something unknown, something greater than the human mind, gives us what we breathe. The stories say that some people have the power to imagine: when the mind is touched by the spirit of another being, it gives form to that contact. In the mind, an image is formed that will be expressed to the people.

“The first stories came to the Dreamers,” he said.

In the First Beginning, the animals talked to the humans. They called humans the Campfire People.

A misunderstanding I’ve heard sometimes is that animals are innately benign, and that the “balance of nature” which before Contact seems to have existed between animals and Indigenous people was a happy thing, was about getting along together, was about mutuality. This is not quite accurate.

I was given a gift which carried, it seemed, danger: possibly to me, almost certainly to vulnerable Athabaskans. Ten years passed before I knew where to lay the gift down so it could return to its source. When I asked for advice along the way (I mean, of people other than Malfa), those Athabaskan women who would actually talk to me about this – very few, and they were elders – would say, without fail: “We can tell you what is true for us. But we don’t know what is true for white people.” We were alluding, cautiously, to great spiritual powers. I realized that I had to learn my own way, while trying not to cause harm.

It is not too much to say that, carrying the small pouch of wolverine bones, I knew I had entered a story, although I didn’t know its shape and, until long afterward, did not know its end. Even so, I knew that it was but an event in the timeless stories coursing through that country, which themselves come before whatever we humans might imagine. A traveler across literary frontiers, I wanted to learn to tell stories. But I also learned something else. I learned that we can tell ourselves the wrong story.

I am thinking about a conversation of more than twenty-five years ago with the late Barry Lopez. He was considering no longer writing for magazines, as he had done to make a living, after having come through a harrowing session with an eminent editor. He had journeyed into the immensity of the Brooks Range, to Anaktuvuk Pass, an Iñupiat village. The piece he turned in was very long. The editor called for drastic alterations. Barry’s desire had been for a prose that expanded both space and time, as he thought his did. The editor would not accept this. The sense of space, especially, would make readers “uneasy,” said the editor — they wanted facts, with which to orient themselves. Barry had composed four essential elements — not “facts” — in an open order: forming a circle, so to speak, around them. The editor suggested organizing the “three of them” hierarchically, in order of importance. “Three,” I said pointedly: “Three and one?” “Yeah,” said Barry, dryly. “Twos and fours always get changed: two terms need a third as mediator.” Even when you’re describing this conflict between more open and more hierarchical forms, he said, even if that’s your subject, they can’t hear it. More to the point, I said, they can’t bear it.

This is not a small point, when you think about it.

Not all stories are formed from beginning to middle to end. Some stories take other forms. For instance, a known Athabaskan story-form has been described, somewhat awkwardly, as having something like beginning-middle-middle-end. Put too simply, four is an organizing number in many Indigenous societies, as three has been in Graeco-Western traditions. In these multi-cultural days, the editor’s mythical “reader” may already understand this.

Here is another example. When Malfa Ivanov was at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, in the early ‘90s, a young woman student came up to her and asked if she was Native. (The young woman may have said “Inuit” or “Native American,” trying to be correct.) Malfa said she was. The young woman said she was preparing a presentation and asked if Malfa did beadwork. Malfa replied that she wasn’t an expert at it, but yes, she had beaded. The young woman said (as I recall Malfa’s anecdote), Oh. Thanks, but I need somebody authentic.

Imagine yourself in Malfa’s position.

A year or two after this account ends, Peter Kalifornsky told me a very old story, a sukdu, in which a starving man out searching for food for his people helps a little mouse over a windfall. He comes upon an enormous shelter and is invited to enter, after first turning three times with the sun. There reside a giant couple: the guardian of the animals and his wife, “the mother of everything over and over,” the mother of the animals. Later, in Fairbanks, I asked the Koyukon linguist Eliza Jones about these giants, whether they appeared also in stories from the Koyukuk River. I don’t recall my question precisely — it may have been about the mother of the animals — but her answer remains with me and has grown larger over the years. She said to me, “A spirit comes to a destitute person in a form he can recognize.”

This account is a work of nonfiction, a narrative of memory and deconstruction, set in 1984, with a flashback to the previous year and a conclusion in present time. The people, places, and events were real and are described as they occurred; the names of towns — Fairbanks, McGrath, Nenana — are as they appear on maps, as are the rivers’: the Yukon, the Koyukuk, the Tanana, the Kuskokwim; but the names of most persons and villages have been disguised for the sake of what remains of their privacy. I’ve employed this courtesy because this is a true account, a sort of mythopoeic travel book which draws from, but isn’t limited by, practices of ethnography, poetics, historiography, cultural studies, and memoir. It does not embellish; nor does it fantasize. But nor does it intend to embarrass anyone but myself. The narrator, who may have been, after all, a destitute person, is a white American traveler drawn into the Alaskan Interior, where she lived and worked among Native people as a poet and where she learned a way to see the country.

Katherine McNamara

Charlottesville, Virginia, January 2022

*Notes:

an itinerant poet in village schools: This was between 1976 and 1983. In 1976, Tobeluk v. Lind (the “Molly Hootch case”) required the State to build high schools in all villages, so that children beyond sixth grade would not be sent to boarding schools, as they had been sent for several generations, depriving them of parenting and cultural instruction during their vulnerable teenaged years. I traveled to a number of these new village schools, as noted in this book; I observed good teachers, but also some egregiously terrible, hurtful teachers, nearly all non-Native. In this work, I tell how Malfa wished to become a teacher, through the old field-based program X-CED. (I wrote about rural schooling for Cultural Survival.)

As has been reported regularly and is currently a front-page story in Canada and the U.S., Indigenous students suffered suppression of language, forced behavioral changes, sexual molestation, even death in boarding schools. A useful timeline of non-Native schooling in Alaska has been assembled by Jane Haigh: https://sites.kpc.alaska.edu/jhaighalaskahistory/history-of-alaska-native-education/.

See also:

Katherine McNamara, Narrow Road to the Deep North

From the First Beginning, When the Animals Were Talking

From the Believing Time, When They Tested for the Truth

photo: A storm coming in over Creamer’s Field, Fairbanks, Alaska, 1984. Katherine McNamara

Storm coming in, Fairbanks, Alaska, 2004

You must be logged in to post a comment.